IP value is business value in Protein Industries Canada programs

- Posted:

Author: Jennifer Jannuska, Director of Data and Intellectual Property

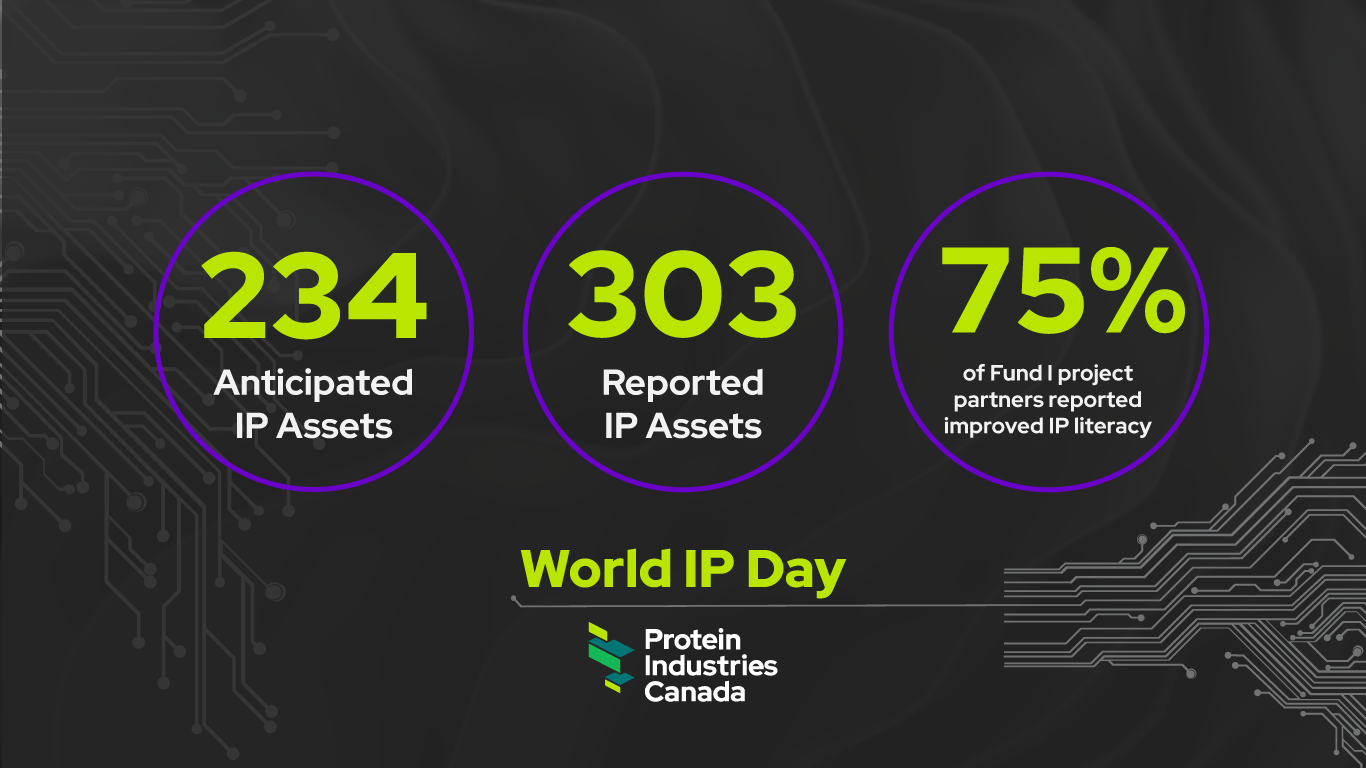

With the announcement of the new Canada Innovation Corporation, there has been a predictable array of critiques of innovation programs, and the discussion has turned to IP assets.

Some have criticized the cluster system for counting IP assets “like cabbages,” saying that we have no particular IP strategy to drive supported companies toward commercialization and no evidence of the value of the IP generated.

Shakespeare described the north star as “whose worth’s unknown although his height be taken.” This is a bit of how IP is approached in the innovation clusters. Admittedly, at five years old, the clusters are doing a lot of height-taking, but let me tell you why this risk can lead to reward.

As an IP lawyer, I spent more than 20 years in private practice counseling Canadian clients on how to get more value out of intangibles. What I learned is that seeing “value”—or what economists see as “value”—from IP takes many years.

Two classic models of IP valuation are litigation value and licensing value. Litigation value speaks to the effectiveness of IP in blocking other later market entrants through litigation, specifically injunctions. Licensing value speaks to rent-taking on IP: whether or not someone wants your technology enough that they’d pay a royalty to use it. But both of these are slow to be seen—not just in Canada, but everywhere.

In my innovation cluster’s sector, plant protein, we are watching the progress of a U.S. patent suit brought by Impossible Foods against Motif. The patent relates to non-meat heme technology, a major building block of Impossible’s plant-based burgers that “bleed." Impossible’s patent application was filed in 2011; it was granted as a patent in 2020. The lawsuit started in 2022. There is also an inter partes review pending from Motif challenging the validity of Impossible’s patent. Bottom line, it is more than a decade since this technology was created, and Impossible still doesn’t know whether its patent is valid, whether it can be successfully enforced against Motif, and whether Motif or anyone else will decide to license it.

The litigation or licensing value can’t be known in a short or artificial timeframe. There are limitations in how we can talk about “commercialized” IP at an early stage. At an early stage, in the absence of litigation value and licensing value, what we can see is how that IP is linked to practical business value.

By practical business value, I mean accumulated know-how within a company about how to make a product using a process, availability and maturity of input sources to make that product, facilities and machinery to execute that process using those inputs—how the companies themselves articulate their brand and their value proposition, relative to Canadian competitors and those abroad. Sometimes the exercise of developing formal IP is an important moment of reflection and articulation of these advantages.

It has not been my experience in the cluster system, or before in private practice, that private sector companies develop IP for the fun of it. In fact, what I see is a huge reluctance to crystallize or pursue IP driven by cost and complexity fears, misconceptions about the availability of formal IP in certain fields and misperceptions of the scope that can be achieved. I see the critics of the system doing nothing but feeding these fears.

What can and does nurture IP development in the face of these beliefs? Mentoring, ideas from other companies and IP education—in short, a collaborative approach. The clusters provide a relatively safe and litigation-free bubble in which to accumulate some of the practical business value that buttresses great IP and makes commercial products possible—that is, validation of a new technology or a new solution while, for the IP, the worth’s unknown.

What you see are numbers in reports—and I can understand why these look like cabbages—but look deeper and see the practical business value:

- Facilities developed: In our program, huge new facilities operating or soon-to-be—Roquette in Portage la Prairie, Ingredion in Vanscoy, Konscious Foods in Vancouver—doing ground-breaking things around pea, oat and fava protein and pushing out lines of new vegan products.

- Innovative products on the market: a Wagyu steak replacement hitting both five-star hotels and 7-Eleven, a fava-based tofu garnering awards and retail shelf space.

- Innovative services on the market: weed sensing from a drone flying overhead.

- Harder, less sexy, work being done on the digestibility of plant proteins, work on the traceability of crops from the field to your fork, removing solvents and other agents from processes for a cleaner, purer product.

- Great jobs will stay in Canada because they are linked to the working of the IP developed here—the institutional knowledge and know-how that wraps around the IP as well as the equipment and facilities that live here.

The north stars are out. The impatience and half-truths around IP aren’t helping, but I’m optimistic about what we have here and would love to see more success through our cluster system and through parallel agencies.