Protein highway forges connections

- Posted:

- Category:

- PIC in the News

An initiative gathers steam to bring agricultural and engineering research together to improve plant protein processing

SASKATOON — Hundreds of students cross the bridge between the engineering and agriculture buildings every day, heading to cafeterias, offices and parking lots.

It’s a pedestrian highway connecting part of the sprawling and populous campus, joining two of the University of Saskatchewan’s highest-profile faculties.

But that pathway is much quieter when it comes to researchers moving back and forth between departments, a quietness that applies to the rest of the university’s halls and walkways.

The same lack of traffic characterizes the research and development flow between universities, agriculture and food industries, and government agencies and departments not just in Saskatchewan, but between all the provinces and states of the Great Plains and Prairies.

When it comes to developing the vast potential of central North America to be a plant protein powerhouse, that’s not good enough, some think.

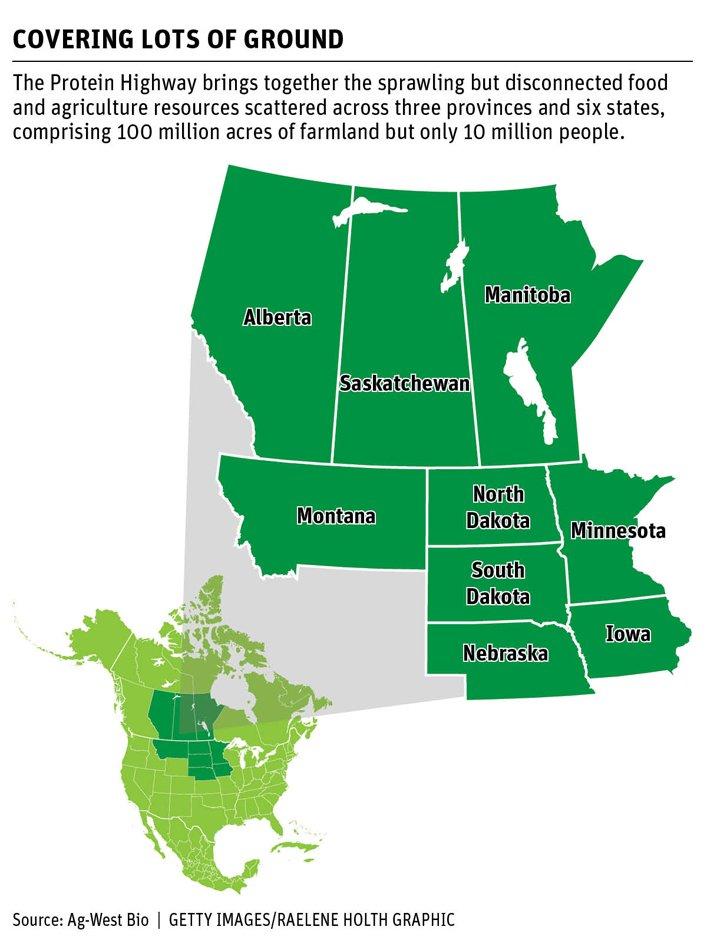

“There was a need to collect together groups from policy, government, leaders, industry and researchers,” said Venkatesh Meda, a bioengineering professor and one of the inaugural directors of the Protein Highway, explaining the network’s purpose. It includes Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Montana and the Canadian prairie provinces.

The Protein Highway’s board of directors plan to hold its first meeting in November, at which point it will begin firming up the connections between states, provinces, institutions, organizations and the private sector.

It’s a big task, but one the Protein Highway’s founders think is key to bringing together the sprawling but disconnected food and agriculture resources scattered across three provinces and six states, comprising about 100 million acres of farmland but only 10 million people.

“There’s a need for cross-connection … particularly the breeders, the genomics people and the processing people,” said Meda, speaking about better interactions he’d like to see just within the U of S.

Across the agriculture-engineering bridge, Bob Tyler, a long-time plant protein researcher with the agriculture department, is hoping to see an acceleration of the commercial development of plant proteins like those from peas, something he’s hoped to see for decades.

“It’s a whole new reality. It has a different feeling,” said Tyler, who is involved with the Protein Highway and has been intimately involved with Protein Industries Canada and Ag-West Bio.

“It’s not (been) for the impatient.”

Plant-based proteins are now all the rage in consumer circles, with most major grocery store and restaurant chains offering meat substitutes on their menus.

Pea protein has been integral to many of the products, such as the Beyond Meat burger, but researchers and developers hope to see other crops also moving into that space.

But that’s hardly a new hope.

“It’s taken this long: 40 years. Better late than never. But sometimes potential isn’t realized until everything lines up,” said Tyler, who has been involved in plant protein research for decades.

Researchers have always, in many places, seen the potential of plant proteins to supply some of consumers’ needs. For more than half a century academics and public and private research and development people have been trying to extract, refine and incorporate the proteins from crops like peas, lentils, fababeans, soybeans and other pulses into mainstream commercial foods. In recent years less obvious sources, such as canola meal, have been added to the mix of potential sources.

But it’s hard and exhausting work to not only fractionate, refine and produce plant proteins, but to then take them along the next steps toward the consumer. That’s where so much potential has never been realized.

Plant proteins must be easy for the processor to incorporate into foods and also to please the fussy palate of the average consumer.

“Texture, colour, taste, aroma — we value these perceptions, these senses,” said Meda, talking about the challenges standing before successful commercialization of plant proteins.

He’s hoping the Protein Highway improves communication between researchers and developers across Western Canada and the central-northern United States. Too many people, too many programs and too many players are stuck in their own silos, often not even knowing what others are doing. With scattered resources, combining forces could help propel all forward.

There are lots of little advances that could be made that could have big impacts, Meda said. For instance, there are no programs in the region to produce protein technology and engineering specialists. People wander into the plant protein space and then have to adapt their mainstream skills to fit. That can make some avoid the area.

“If I tell an engineer to compare and contrast aluminum and iron, it’s easy,” said Meda.

“If I switch those materials with corn and muffin mix, he gets stuck. He can’t do it. But it’s the same thing.”

There is also a lack of commercial scale protein extraction plants available to agriculture and food producers, among other needed facilities.

The Protein Highway was launched by the Canadian consulate in Minneapolis in 2016, after its trade commissioner and staff saw the potential for “pre-competitive” co-operation to help central North America develop the crops and ingredients that could play a growing role in future food trends.

That future has arrived sooner than expected, with the plant-based revolution occurring just as the Protein Highway is getting established, but that makes their work more timely and engaging.

“I think there’s a lot more reality to it this time,” said Tyler, looking back over the decades of research leading to this point.

“The demand is there. The visibility is there. The public awareness of protein is so much bigger now.”

Now it’s a matter of tying together the disparate pieces of research and development across state and provincial lines, across public and private sector divides, and between research and university departments that are accustomed to staying within their own buildings and silos.

That’s what the Protein Highway’s players are setting out to do.